Witchy Workshop Postmortem - Tips to Keep Your GM:S Project From Scaring You

Witchy Workshop is a physics puzzle game where you play as a dog and often set things on fire. If you've played games like The Incredible Machine, you're probably familiar with the general idea: strategically place a series of parts in the right places, hit play, and hope the comically over-complicated machine you've built achieves the goal of the puzzle. It's a genre a lot of people have nostalgia for.

Perhaps

due to this nostalgia, I think a lot of the design in similar games

like Contraption Maker

is fairly conservative. While

limited by budget and scope, we've

added magic and elemental

systems, complex

logic for puzzle goals, and

broken somewhat

with the standard interface

after reexamining

the assumptions

of past games in the genre.

Accessibility is a key

concern with more 'nostalgic'

UIs,

for those unfamiliar with PC games but

also those who have

a hard time with standard input methods

due to injury or disability.

One of my eventual goals is to allow for gamepad

support and fully remappable

controls. For

now, we've added keyboard

shortcuts for almost

everything and added some

accessibility-related video settings (outlines, disabling the

background, simpler fonts).

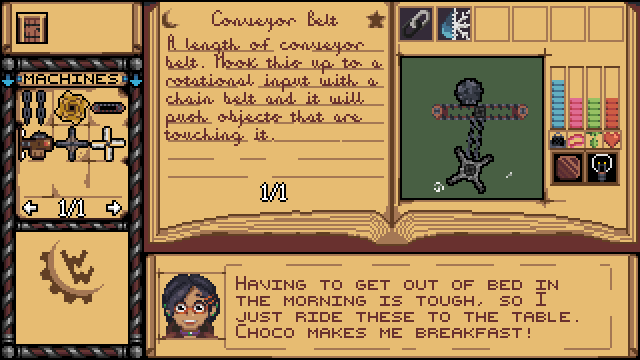

We have tutorials to walk

players through the various mechanics, but each

puzzle piece

is also

described in detail in the Codex; if

you forget how something

works, you can go look it up!

Prior to the development of Witchy Workshop, my girlfriend had almost no programming experience, whereas I only had a couple college CS classes I took for some academic variety. I started with GMS around 2015 through Derek Yu's GM7 (!) TIGSource tutorials, but didn't really do anything with it for a while. Once we got serious about working on something together, I started teaching her what I'd learned, and meanwhile began development of a level editor. The level editor turned into a game by itself, and roughly two years after development began, we've finally released Witchy Workshop.

I've found the best "postmortems", as they are generally called, to have broadly applicable principles in mind, rather than focusing on particularities that are specific to the developer's game. Here are some little things I wish I would have known when I started!

Build an external data workflow ASAP

This is by far the most important thing we did. I guess it's not strictly necessary to work with a lot of external files to release a data-heavy game – for example, Undertale stores much of its dialogue in an enormous, terrifying switch statement. Everything in GML, though, is much easier if you understand data structures, and the jump between data structures and the use of JSON, CSV, and so on isn't a tough one to make.

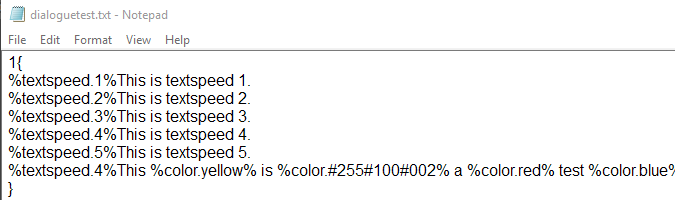

Witchy Workshop doesn't have a lot of dialogue, but the game it takes the majority of its codebase from does, and so my first big self-imposed GML task was to write a dialogue engine. My first attempt at dialogue storage was a simple text file: a number specifying the event, and text in brackets, with “special strings” for adjusting color, text speed, and so on as the dialogue progressed.

It wasn't until I next tackled saving and loading levels that I realized I didn't have to do everything myself. GMS has native support for JSON, and later I came across an excellent script by JujuAdams allowing for 1.4 CSV import without having to write a parser (it seems simple, but getting it right is really hard – even GMS2's implementation has a lot of problems). Turns out, a lot of people already know very well how to use a spreadsheet application, and JSON isn't that difficult to write for a beginner with a little practice.

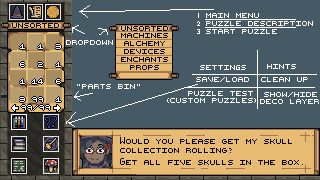

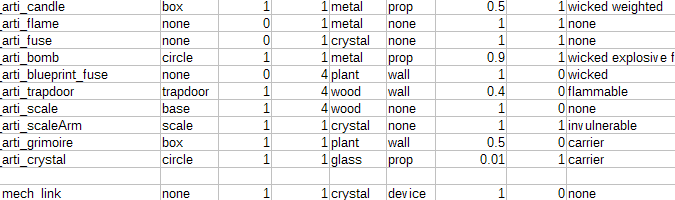

As

a result, if you open our included files folder, you'll find about 50

JSON and

CSV files. The GUI, event triggers, state machines, video

resolutions, audio metadata, material data, piece data, and

puzzles are stored

as external files. Building

the UI in particular with JSON allowed us incredible flexibility:

disabling or hiding interface elements, assigning hotkeys, adding elements to groups, and so on saved countless hours. It

also led us naturally to following

patterns like object

composition and inversion of

control which are not otherwise intuitive or

accessible in GML.

Without this framework,

designing

and polishing the interface would have been punishingly difficult.

Few Photoshop

or Aseprite GUI mockups

survive the

realities of playtesting.

If you're new to GMS, look at it this way. Using external data in your project is sort of like mechanical advantage – the phenomenon which makes pulleys and levers better at lifting than simply trying to pick things up off the ground. How much work would you put in to type a ten-row spreadsheet's worth of data into your project directly? Not much, right? But how about a hundred rows? A thousand?

As mentioned before, this isn't even really hypothetical: a hundred rows sounds like a lot, but what about ten different sets of data at ten lines a piece? Finding points where you can maximize your advantage – get more out of less – is one of the fundamental strategies of programming, both in optimizing code and optimizing the way you write it. Make the computer do the work! It's really good at it!

We

eventually created a unified “asset

list” system,

giving each asset a map to store their name, type, hash, and

other properties

to allow for live UI

changes. That

isn't really necessary, especially

if your GUI is fairly minimal, but

you'll be happy to have it

when you find out an element

is one pixel too wide.

The important

parts

are a mechanism to

load, and provide access to, an external file in one line, and

a mechanism to pinpoint

the desired data in the

file. For CSVs, that will generally be your row, and for JSON files,

it

will generally be an individual map.

Just make sure whatever you write is really simple to use – one line and your data is loaded, one line more and you have a reference to what you need. You're way more likely to use it this way; not just because it's easier, but because psychologically, it's easier to stick with a system which isn't frustrating.

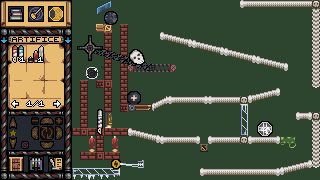

Making a deterministic game around GMS’s Box2D implementation is more difficult than you’d be led to believe

I'm throwing this one in here because while it's super niche, it's really something people should know. Pretty much everything we had read about GMS’s Box2D implementation stated it was (at least for a given platform) deterministic - from simulation to simulation, the results would be identical. It’s not really “necessary” for a physics puzzler to be deterministic, but it’s expected; you shouldn’t be able to win a puzzle with a given solution only half the time. Witchy Workshop, then, was largely built on this premise, and it’s correct, for sufficiently flexible values of “correct”.

About halfway through

development, we ran into a strange issue we should have identified

earlier. Box2D was flipping the sign of physics fixtures' collision normals between simulations. This would lead to, for example, bouncy

objects “hugging” each other, their direction of force sometimes

facing each other instead of away from each other.

Unsure why this was happening, we tried everything we could to narrow it down. A crucial data point emerged: it never happened when the game had only been run once.

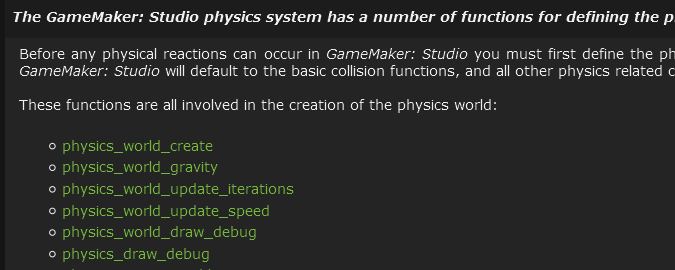

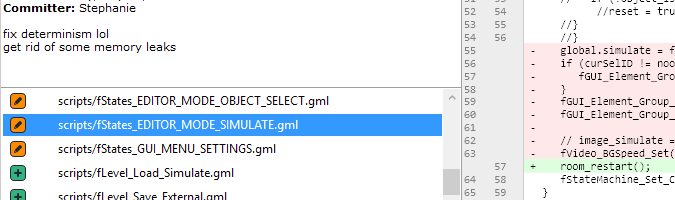

Since restarting the game fixed the issue and nothing else did, we suspected an innate problem with reusing the physics world, which is initialized per room in GMS. We tested our hypothesis by changing rooms, which rebuilds the physics world, and the normals issue disappeared entirely. Unfortunately, while you have to manually build the physics world with physics_world_create, there’s no way to destroy it.

We brainstormed various world-destruction solutions, like creating a new room on simulation and moving everything there. When we went out to lunch one day, it struck me that room_restart might work just as well without having to create hundreds or thousands of new rooms per playthrough, and when we returned I tried it out. Disappointingly, it seemed to have the same small (~4KB) effect on memory usage as creating a new room, but it worked, and it was a significantly simpler solution.

The task of keeping all those objects intact seemed fairly monumental, since I didn’t want to mark all our objects as persistent. Respawning them, on the other hand, would mean having to account for transformations the player had done to each piece after they were placed. We also didn’t want the player to notice the transition. I eventually realized the task of moving the parts was as simple as saving the game to a special filename when the puzzle is started, restarting the room after simulation stopped, then loading the special save when the player returns to tweak the puzzle.

Making this look good required a few tricks at the time, like saving the screen at simulation start and displaying it again as the new objects execute their transforms on simulation end, but it appears seamless. We were later able to remove this after refactoring the transformations to finish in a single frame, but it's a good technique to know about (it's also used for the left panel during simulation).

Use source control! (please)

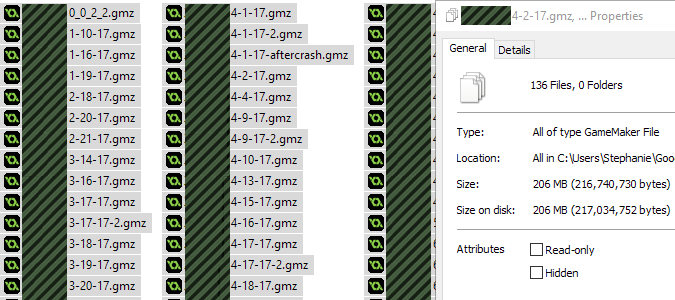

We knew Dropbox was notorious for corrupting GMS projects, but as our codebase grew, we needed a way to easily collaborate. For a while, we made do with Google Drive, exporting .gmz files as we went to make sure nothing got too messed up. Surprisingly, this actually sort of worked, but it wasn't really ideal. At the time, Git wasn't something either of us were familiar with, and GMS 1.4's built in source control seemed really confusing.

In November, I came across this helpful article detailing how to use GMS with external source control. Within a few days, we had the repo set up, and this eventually allowed us to fork the codebase and create Witchy Workshop with a minimum of fuss. I've heard rumblings GMS2's project files are much harder to resolve main project file conflicts on collaboratively, which is unfortunate, but can't speak to that as we stuck with 1.4. Just don't accidentally push your forked project upstream and almost give yourself a heart attack like I did.

Sometimes reducing scope... is fun?

When you get into game development, you learn very quickly that everything is harder than you think it is. The common reply is to reduce scope. The common response is "that doesn't sound fun at all!". It's true making a little 2D shooter is going to be less thrilling than your dream AAA MMO with an open world and epic storylines and procedurally generated, science-based voxel dragon spaceships. But it doesn't necessarily have to be a slog.

Witchy Workshop was originally intended as a side project so my girlfriend could learn more GML. She was embarrassed to even ask me if she could work on another project, and kept her work under wraps for a while. She knew the new project honeymoon period is addictive, and she knew I knew. Everything took longer than expected, but we (and our codebase) have benefited greatly from the experience – and now we have a released game with a lot of room to grow.

Never in my wildest dreams would I have considered turning a 2D

run-and-gun

level editor into

a physics puzzler. But we

were always sort of halfway there. So

in the future, I'll

always

be thinking about how

existing systems can be adapted, either

as proof-of-concept or full games.

Having a very different

project as a palate cleanser is also really nice. I hope some of these tips were helpful for yours!

Get Witchy Workshop

Witchy Workshop

Use spells, machines, and alchemical devices to solve the Red Bean Witch's magical physics puzzles!

| Status | On hold |

| Author | Deerbell |

| Genre | Puzzle |

| Tags | Cozy, Dogs, Female Protagonist, Magic, Non violent, Physics, Pixel Art, Singleplayer, Spooky, Spoopy |

| Languages | English |

More posts

- Witchy Workshop 1.1.1 - Release NotesApr 28, 2019

- Witchy Workshop 1.1.0 - Release NotesFeb 03, 2019

- Witchy Workshop 1.0.1 - Release NotesDec 01, 2018

- Witchy Workshop 1.0 has been released!Nov 24, 2018

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.